Beagle’s Historical Retrospectives

The Story of the Only Time a Country Has Lost Orbital Rocketry Capability

And now, for something completely different.1

How does a country have, then lose, their homegrown orbital rocketry capabilities? There have been over a dozen countries to create orbital rockets, then fly them successfully, but only one completely removed itself from any space ventures following a successful orbital vehicle: The United Kingdom. The UK launched the Black Arrow vehicle a total of just four times but canceled the program even before it reached its greatest success: launching the Prospero satellite into Low Earth Orbit.

NASA, for one, was extremely interested in the Black Arrow vehicle, as launching from Australia offered a range of opportunities to launch into different orbits — especially with differing inclinations — than was possible in the United States from the Wallops Flight Facility (in Wallops Island, Virginia) or from Kennedy Space Center (in Florida), but despite the British program’s enthusiasm for NASA money and support, Parliament never gave them the chance to take advantage of it.

Black Arrow is an interesting vehicle. As with many vehicles of the time, it was built off the back of a ballistic missile, this one being the Black Knight suborbital vehicle. It launched a total of four times, two successes, and two failures. The first launch occurred in 1969, with the R0 vehicle (apparently, they followed the Python naming scheme!), which was launched without a payload or a third stage. The first stage suffered a thrust vector control failure and began to spin out of control due to an electrical fault in the first stage’s engine. Just over a minute into flight, safety teams were forced to detonate the Range Safety Ordinance and blow the rocket into bits (kablooey #1). This was not an uncommon failure for early rockets, especially those with complex engines, as the Gamma-304 Type-8 was. The R1 vehicle would have to replicate the same profile. While it was initially slated to perform the first orbital launch, British scientists were unwilling to trust their payload to an unflown second stage — which is a valid concern and is still somewhat common practice today (see Rocket Lab’s Just Testing and Still a Test missions for Electron). The R1 vehicle performed flawlessly when it launched a year later, in 1970, and both stages burned to completion.2

Upon completion of the suborbital test flight, the go-ahead was given to the teams to mate a payload, named X-2/Orba, and mate a fully functioning Waxwing third stage. However, the R2 vehicle’s second stage suffered from a failure, leading to a premature shutdown of the Gamma-304 Type-2 engine about 13 seconds early (resulting in kablooey #2). While the Waxwing fired perfectly, the Orba satellite was still left under orbital velocity. This failure put the program’s shortcomings squarely in the sights of Parliament, and just months after the failure of R2 in September of 1970, the Black Arrow program was on the chopping block. Sure enough, before the program even had an opportunity to redeem itself, it would be canceled by Parliament in July of 1971. Luckily for the teams, the completed R3 vehicle had already been shipped to Australia a mere few days before their budget was slashed and their project cancelled, and for that reason – and that reason alone – they were allowed to have one last attempt to place Britain’s first satellite, dubbed the X-3/Prospero, into orbit.

R3 worked flawlessly. Powered into orbit in around 10 minutes’ time, Prospero became the first British satellite launched by a British vehicle to enter orbit. Prospero, and presumably its Waxwing upper stage though I couldn’t find anything to confirm this, still remain in orbit to this day. Prospero would be fully operational for only around 2 years, as its tape recorder suffered an electrical fault following a Coronal Mass Ejection. Its radio chirps could be heard by amateur radio operators until at least 2004, though, as found by a BBC show. There is still a chance that we could still hear the chirps from Prospero today, though it is likely being drowned out by other traffic.

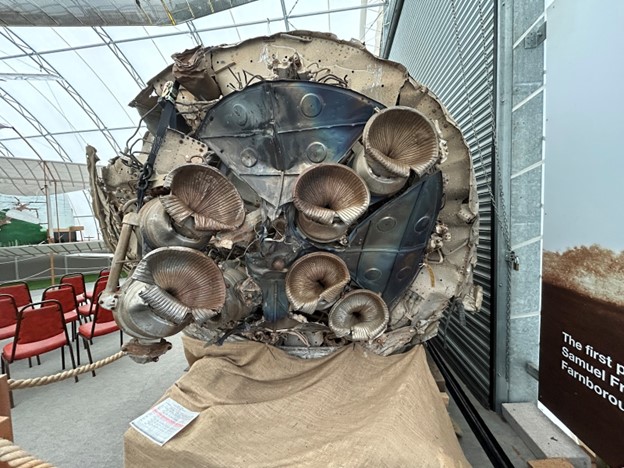

I was blessed with not one, but two excellent opportunities to learn more about the Black Arrow while I was in England in March: The Science Museum in London, home to the unflown R4 vehicle, a fully produced Black Arrow that was never shipped to Australia before the program’s cancellation, and the Farnborough Air Sciences Trust, home to the flight-used R3 first stage (as seen in the above photographs), recovered from the Australian Outback some years after its flight.

What I discovered, though, was that even the British have largely forgotten their own history of spaceflight. There was shockingly little material on the R4 vehicle, despite being fully intact; just a single panel of information, and the vehicle itself swung overhead, seemingly longing for someone to notice it.

All photos taken by me at the Science Museum of London, March 2024

Parliament and the UK space program had received very little interest in the Black Arrow vehicle commercially, and Parliament canceled it with the stroke of a pen despite a looming deal with NASA for a ride-swap agreement between Black Arrow and NASA’s Scout launcher, a similarly capable vehicle. Scout flew until the early 1990s and notched dozens of flights in various iterations, while Black Arrow, much its equal, was canceled over 20 years before, and the ride-swap deal would fall through as a result of the cancellation. Britain themselves would build just one more satellite in its series, the X-4, launched aboard a Scout, but then that satellite series too would be canceled. Ah, budget cuts, the bane of all things spaceflight related… (for more recent examples, see the VIPER rover that they cancelled just months before its launch and are literally going to deconstruct for parts… maybe. We’ll keep everyone posted as that story continues to develop.)

Black Arrow had aspirations not just inside the UK, but outside of it, too. Its launch was a major collaboration between the UK and Australian governments, occurring from a site in Woomera, and the Woomera launch facilities have since largely sat vacant, as the UK never returned with a launch vehicle. Additionally, while countries like the US and USSR celebrated their space ventures, the UK (and to a lesser extent, France before Arianespace) rarely discussed such things, instead seeing them as merely military matters, and removing them from the public eye, cursing them to a life and legacy of obscurity. Something I noticed when I was in London in March is that when young students — their future engineers and scientists — go to places like the London Science Museum, they are cruelly unaware that their own country ever went to orbit, as it’s but a footnote in the majestic history of space exploration, which frankly kinda broke my heart.

But what if things had been different? Before the cancellation of the program, there were already plans to build at least one more Black Arrow, designated R5, of a current design, but beyond that was theorized a massive upgrade that would’ve placed Black Arrow solidly in the small launch market, boosting the payload capacity further into a market that even today is only serviced by a select few providers – primarily Rocket Lab’s Electron vehicle.

Even further down the line were theorized liquid hydrogen upper stages for a more powerful Black Arrow successor, one I personally like to dub the Black Duke (as it would’ve been smaller than the theorized Blue Streak/Black Arrow hybrid codenamed the Black Prince). This potential upgrade, though, likely never would have made it off the drawing board without heavy support from both the UK and Australian governments, as launching from the hot Australian outback is rather painful for launching anything, much less something with colder-than-ice liquid hydrogen, but it would have put British rockets likely on par with the venerable Atlas vehicle that NASA used heavily (see the successor of Atlas, the Atlas V, still flying today!)

Would Black Arrow have survived, had it lasted into the era of commercial satellites that prospered just a few years later, truly beginning in the early 1980s? I would like to think so, yes. I feel that it would have thrived in that era, as early commercial satellite providers likely could have taken advantage of the Black Arrow to place satellites into highly inclined orbits to be able to provide communications in places like Britain and Australia, but instead those satellites would be forced to launch aboard the Atlas vehicle. Perhaps Black Arrow was doomed to fail, alas. But it was an idea, a brilliant idea, perhaps one ahead of its time. It truly is a shame that its own people have forgotten about it.

Author’s Notes

This is not, in fact, something that we normally write here at Max-Q. However, during my freshman year at UAH, I was gifted the opportunity to travel to London and write a research paper. As any budding aeronautical engineer would, I decided to write on an aerospace topic.

Initially, I had planned to write on the differences between 1960s and 70s American and British rocketry… but soon realized that that was such an in-depth topic it could easily be somebody’s thesis — maybe even a master’s thesis — and way above my (theoretical) pay grade. (Insert “you guys are getting paid for this?” joke here)

With the blessing of my boss here, I turned that paper into one that we could publish here and is more in line with how I write for fun. (Also to avoid plagiarism, even if it is my own work; another reason that this article will (hopefully) remain unmonetized, even after future website updates/upgrades.)

If you want to read this article in its original, much more professional form, you can find that here: http://libarchstor2.uah.edu/digitalcollections/exhibits/show/uah-in-london/black-arrow-orbital-capability

I also have a poster version of that professional article, so if you want the really condensed version and you want to like print it out or something, you can find it here: https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1TkqT0hCACqFgSlZImBHZeW06cD0TVdBqnGSRQzI84eI/edit?usp=sharing

As I wrote on both previous versions of this work, I continue to offer my biggest thanks to the trip coordinators, my professors at the University, and to the Farnborough Air Sciences Trust (better known as FAST) for letting me use photographs of their R3 vehicle.

Hey, y’all! I’m Ethan, I go by Beagle, and I write space. I am a part of the Max-Q News team, as well as one of two hosts for the Max-Q Podcast!

Leave a Reply