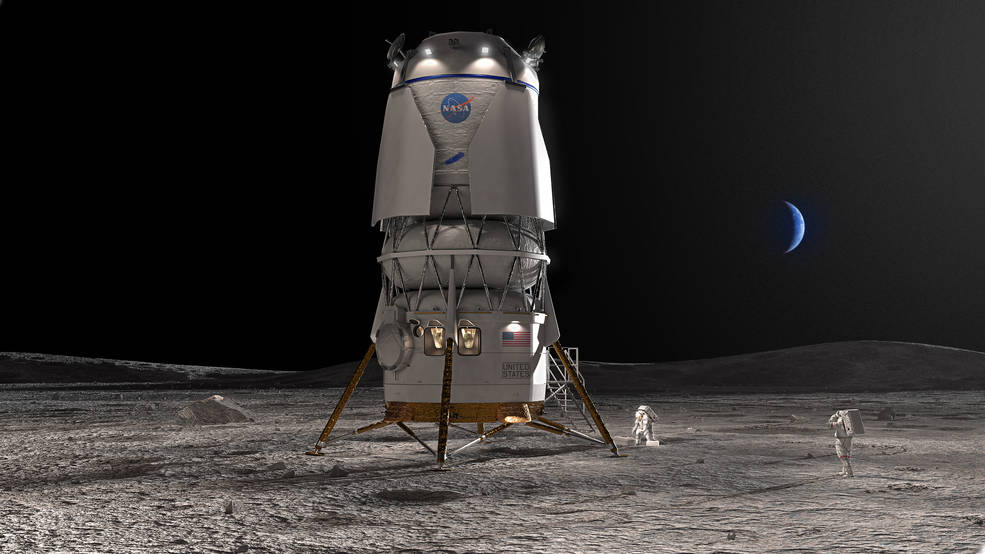

On May 19th, NASA announced they have selected Blue Origin to develop a human landing system for the Artemis Program. Blue Origin will take the remaining spot of two private contractors tasked with developing the lunar landers for NASA’s new era of lunar exploration alongside SpaceX’s Starship, which was selected in May of 2021.

Credit: Blue Origin

Blue Origin has been awarded $3.4 billion to develop their Blue Moon lander for an uncrewed demonstration landing and a crewed landing on Artemis V. As of writing, Artemis V is currently scheduled for 2029.

Blue and Co.

Blue Origin’s Blue Moon lander was originally revealed in 2017 as an robotic lander capable of bringing payloads to the lunar surface. It was advertised to launch on Blue Origin’s upcoming New Glenn rocket and be able to deliver 4.5 tons to the lunar surface.

Credit: Blue Origin

When NASA first released the competition for two HLS service contracts to provide crewed lunar landers, Blue Origin collaborated with numerous other aerospace companies to submit a crewed version of Blue Moon under the “National Team”. The National Team consists of Blue Origin, Lockheed Martin, Draper, Boeing, Astrobotic, and Honeybee Robotics. Though they did not win the first selection award, NextSTEP Appendix H (SpaceX’s Starship HLS was selected to land crew for Artemis III and Artemis IV), they were in “second place” and had a clear path forward for the second selection, NextSTEP Appendix P.

Reasons for Selection

NASA released a selection statement in conjunction with the proper announcement, where they highlighted many aspects of Blue Origin’s proposal and approach to HLS that gave the most advantageous position for NASA and Artemis. Blue’s plan is to conduct multiple pathfinder landing missions starting in 2024 to gather in-situ data while developing the lander, ideally demonstrating their lander technology years before the uncrewed demonstration. With this development approach in place, Blue Origin also plans to perform the uncrewed demo with a lander fully equipped to support a crew, which is beyond NASA’s requirements for the uncrewed demonstration. NASA notes this as a “significant strength” of Blue Origin’s proposal.

On the opposite hand, the selection statement also provides the analysis of the competing proposal by Dynetics. Dynetics also had submitted a proposal for the 2021 selection, but was also rejected. The selection statement points out a “significant weakness” in Dynetics’s proposal as there is major uncertainty about meeting the requirements for Artemis V’s planned mission profile, including “Appendix P utilization cargo and the Exploration Extravehicular Activity (xEVA) suit”. Their proposal also had not clearly demonstrated meeting “several requirements” for its crewed demonstration, resulting in another significant weakness.

Price assessments were calculated for both proposals. Blue Origin’s exact assessment was $3,419,345,052.35 and was deemed “reasonable and balanced”. The assessment for Dynetics was not disclosed in the selection statement. While also deemed reasonable, it was noted to be “substantially higher in amount than the competing proposal”. That gave NASA both a technical and financial justification to award the Appendix P selection to Blue Origin over Dynetics.

How Blue Moon Will Work

Blue Origin and the National Team will develop two vehicles for Blue Moon. One will be the crewed lander itself, and the other a “cislunar transporter”, acting as a fuel tanker for the lander. The lander is planned to launch on New Glenn, which itself is planned to debut in 2024-2025. It will launch directly into the planned near-rectilinear halo orbit (NRHO) around the moon and remain until it will either dock to the transporter for fueling or to the Lunar Gateway, NASA’s planned lunar space station and “base camp” for Artemis crew. The transporter will launch to low Earth orbit (LEO) and be fueled by subsequent dedicated fueling missions. The transporter will then carry the stored propellant to NRHO and rendezvous with the lander to refuel it for multiple missions. The transporter then returns to LEO and repeats the process.

Credit: Blue Origin

The lander itself will meet with its crew at the Lunar Gateway. Four astronauts will launch aboard NASA’s own SLS rocket and Orion spacecraft, dock at the Gateway, and two will transfer to the lander. From there, the lander will depart the station and begin its journey to the lunar south pole, and land on the surface.

An interesting note about the design for Blue Moon is that it plans to use hydrogen and liquid oxygen as its propellants. Hydrogen is a very efficient fuel, but its main drawback is that it must be stored at very low cryogenic temperatures to prevent it boiling off. The technological and mass requirement to keep hydrogen in a usable state for long duration missions beyond LEO have often been too much cost for the performance. For example, the Apollo lunar landers used hydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide as propellants because they are much easier to store in a sustainable manner, which outweighed the performance benefit of using hydrogen. Stated in their own press release, Blue Origin intends to “move the state of the art forward by making high-performance LOX-LH2 a storable propellant combination” and making hydrogen a viable propellant for long duration missions.

Two Landers with One Goal

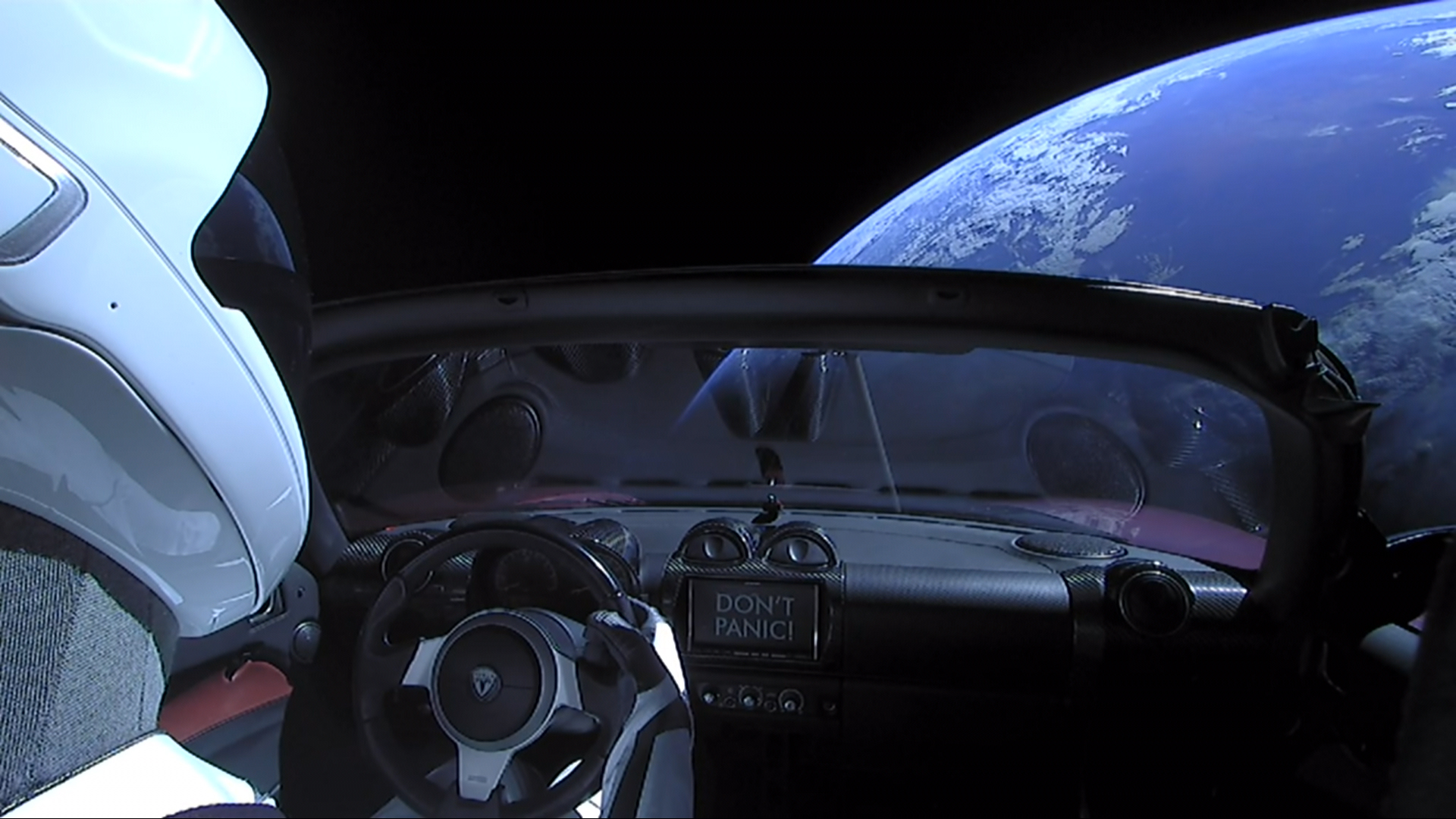

As has been mentioned multiple times, the selection of Blue Origin to develop a crewed lander was one of two selections by NASA for the same purpose. The other lander, selected in 2021, is SpaceX’s Starship. Starship is planned to follow a similar plan to Blue Origin’s for their path to the moon. They will fly an uncrewed demonstration mission (perhaps multiple at SpaceX’s discretion) and then support Artemis III, the first return of humans to the surface of the Moon since Apollo 17, 50 years ago. NASA also exercised an option in its initial award to SpaceX and contracted Starship to also support Artemis IV.

Credit: NASA/SpaceX

The Artemis Program intends to land on the moon several times beyond Artemis V, ideally reaching a yearly cadence of moon landings. How many Artemis missions there will truly be is unconfirmed, but we do know of at least seven more SLS vehicles either in production or planned. This likely sustains the program up to Artemis 8. That also leaves at least three Artemis missions unclaimed by either HLS company. While the specific method for determining the lander for every mission past Artemis V is unclear, it would be safe to assume that the landers will either alternate service or be awarded contracts based on mission requirements that cater to their unique capabilities.

Having two separate landers is a departure from the norm of the Apollo Program, which used a single lander design for every mission. This is a clever departure, however. It follows the same philosophy that drove NASA to select two commercial spacecraft for launching astronauts from American soil. Redundancy and competition. Having two options competing for contracts drives innovation and technological advancement, because neither company can become complacent knowing they have NASA’s programs in their pocket. NASA can simply start awarding the more diligent company contracts and leave the other catching up.

Having two landers also provides security for a sustainable program, as one vehicle can substitute for the other if the latter were to experience issues or delays. Lisa Watson-Morgan, a manager of the Human Landing System at Marshall Space Flight Center remarked “Having two distinct lunar lander designs, with different approaches to how they meet NASA’s mission needs, provides more robustness and ensures a regular cadence of Moon landings . . . This competitive approach drives innovation, brings down costs, and invests in commercial capabilities to grow the business opportunities that can serve other customers and foster a lunar economy”.

Leave a Reply