April 20th is known for many things. One of those things is now the first day of the Age of Starship. At 8:33 AM local, the largest and most powerful rocket ever leapt from its pad in Starbase, Texas on Starship’s first Integrated Flight Test.

Journey to Flight

This first launch of Starship will be known as a testament to the perseverance of the Superheavy booster, Booster 7 (B7). Prior to flight, this booster suffered multiple severe failures, yet had been repaired after each and has now performed the first ever flight for a Superheavy. On April 14th, 2022 during B7’s first cryogenic proof test, the downcomer, which feeds the liquid methane from its tank down to the raptor engines, had buckled and collapsed. Soon after, SpaceX opted to replace the downcomer instead of scrapping the booster, which was a decision unexpected to most outside observers.

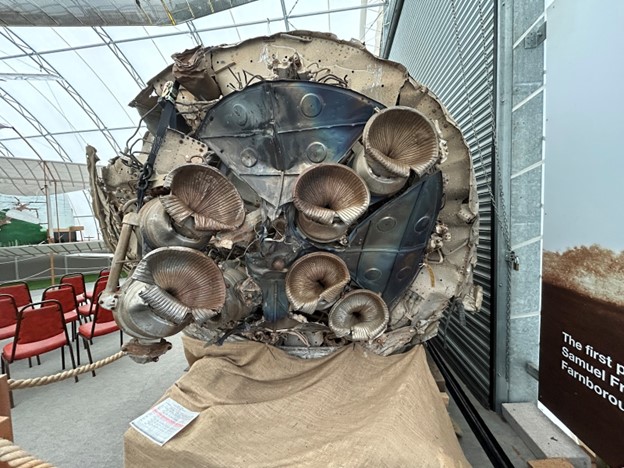

On July 11 of that same year, B7 was undergoing engine testing with all 33 raptors installed. It attempted a spin prime, but instead experienced a fiery anomaly, causing severe damage to the bottom of the booster and the Orbital Launch Mount (OLM). Elon Musk responded to this anomaly by stating 33 engine spin primes will no longer be performed simultaneously:

B7 was once again repaired, and went on to perform seven static fires including a 31 engine full duration fire at 50% thrust, aiming to validate both the booster’s ability to light all engines for launch and to verify the fondag-reinforced concrete below the OLM would survive a launch attempt.

Credit: NasaSpaceFlight/Nic Ansuini

DISCLAIMER FOR ALL FOLLOWING SECTIONS: As this is the very first flight of a developing program, much of the “analysis” done in this article is to be taken not as fact, unless it directly references information provided by reputable sources, such as SpaceX or Elon Musk. It is possible, if not likely, that speculation and assumptions made in this article will be proven inaccurate. Until an official analysis is published or presented, all “analysis” should be taken as speculation, even if it is supported by evidence.

Flight Recap – Vehicle

The flight was known to be off-nominal nearly immediately. As per SpaceX’s planned countdown timeline, engine ignition was supposed to occur at T-8 seconds, with liftoff at the normal T-0. Instead, the engines began igniting around when the clock reached T-3 seconds. The vehicle remained on the pad until finally lifting off at about T+5 seconds.

Credit: SpaceX

Soon after liftoff, the SpaceX webcast began displaying telemetry from the vehicle, immediately, it is shown that three engines had stopped working during the ignition and liftoff sequence. At around T+30 seconds, a series of flashes and visible debris appear at the bottom of the booster, signaling an engine flaming out and possibly exploding.

Credit: SpaceX Webcast

Following this explosion, a fire can be seen trailing out of one of the hydraulic power unit (HPU) aero covers. The HPUs are integral to the booster as they provide the power for the gimbal authority of the center engines. One of the two HPUs likely was damaged here, leaving only one source of gimbal authority left. In spite of the disconcerting explosion, B7 continued on flying.

Credit: SpaceX Webcast

The flight proceeded through initial ascent and reached Max-Q, where aerodynamic forces on the vehicle are strongest. The vehicle passed through nominally, however Max-Q was supposed to occur at T+55 seconds, however the callout and velocity were received nearly 30 seconds later. This signifies a significant underperformance of the booster, likely due to the engines being lost.

Credit: SpaceX Webcast

Soon after Max-Q, the rocket suffered another explosive event in the aft section. Only a short time later, the stack began to tumble off-axis. This means that the booster lost control authority at some point in the flight, either due to HPU failure or due to loss of raptor control.

Credit: SpaceX Webcast

The stack continued to flip uncontrollably for another 90 seconds before it exploded, ending the flight. In total, up to 11 engines failed during the flight, while 22 remained operational. The vehicle reached an apogee of 39 kilometers and maximum velocity of 2157 km/h.

To help visualize the numbers and data gathered in this flight, Reddit user u/jobo555 created a third-party telemetry subplot using the data that was shown on the webcast:

Credit: u/jobo555 on Reddit

Although the flight did not reach space, or even stage separation, it was a major success for SpaceX and the Starship vehicle. On both the webcast and a Twitter Spaces session with Elon Musk, the main goal was repeatedly stated to be getting off the pad without it being destroyed. For the most part, that was accomplished, and all the rest of the flight path was a bonus for their efforts.

Flight Aftermath – Stage Zero

Although it was not entirely destroyed, the OLM and surrounding launch site did not have a perfect flight, and surely did not come out unscathed. It is beyond doubt that the concrete below the OLM, as feared by many, did not survive the thrust of B7 at full power, and practically exploded into thousands of concrete chunks that flew in all directions.

The area directly under the OLM, as seen in the tweet above, has been dug into a crater multiple meters deep. Groundwater can be seen in a pool next to the mount leg on the left, meaning this crater has breached or is very close to breaching the water table in Boca Chica Beach. The two legs in the foreground of the image are supposed to be connected via reinforced concrete. However, as can be seen, the concrete had all been stripped away leaving exposed rebar. As far as official word goes, it is trending that the OLM is not beyond repair, and will remain for future flights:

Another major area of concern for the OLM is the ring itself. In this tweet by Starship Gazer, the extent of the damage do the OLM ring is apparent:

In another post, pictures of the OLM show multiple blast doors on the booster quick disconnect housing and the ring itself have been torn off. The launch pad itself was not the only are on site that received damage. Included is another post showing the housing for the chopstick arm power unit. At this time, the extend of the damage to the power unit itself is unknown, however it is obvious several pieces of concrete penetrated the housing, and some flying all the way through given some angles show daylight from both sides. Fortunately, on April 24th, the chopsticks and ship quick disconnect arm both successfully returned to their default positions, boding well for the overall health of the tower’s systems.

Starship Gazer also captured good pictures of the Orbital Tank Farm. Massive dents can be seen as the tanks were not spared by flying concrete. Elon confirmed on Twitter Spaces that these tanks were damaged enough to require replacement.

One other structure sustained damage from this flight as well. SpaceX’s first ever flight prototype, Starhopper, nicknamed “Hoppy” by the community, also sustained impacts from the power of the launch.

Credit: Starship Gazer

Starhopper has been a resident in Starbase since 2019, every single prototype vehicle that has been tested has passed by Hoppy at the entrance to the launch site, where it stands today as a water tower, PA system, and as a source of light for the site. The outer skin of stainless steel was peeled away by the blast of the launch, but the actual tank structure held firm. At this time, aside from some dents, it does not seem like Hoppy took any major direct hits from concrete.

The damage was not localized to just the launch site itself either. On the public highway just outside the facility, dozens of media members from across the internet including Everyday Astronaut, Cosmic Perspective, John Kraus, NasaSpaceFlight, LabPadre, and others all had remote cameras set up to catch photos and videos of the launch from up close and personal. Some were also allowed to set up their cameras on the launch site itself. The photos published so far already well capture the destruction that ensued following liftoff.

The camera setup for EpicSpaceflight, known as the Hoop Cams, captured themselves being directly impacted by flying concrete, seen below:

The clips show the setup being pummeled by concrete, both shattering the solar power cell and even damaging the camera’s color filters, causing some footage to be shot in pink, green, and monochrome.

Concrete was sprayed out from all directions. From a drone view of liftoff posted by SpaceX on Twitter, debris can be seen pelting the surrounding landscape and the water off the shore for several seconds, including some very large chunks shown making large splashes in the gulf, as seen below:

From this image it can also easily be seen just how large of a debris cloud this launch produced. This is at about T+10 seconds, and the rocket still has not cleared the tallest point in the debris cloud. The launch tower is no longer visible. The pulverized concrete and dust reached so high that the winds blew it all across the land, especially in Port Isabel where Everyday Astronaut was spectating, and South Padre Island (SPI).

Credit: MaryLiz Bender

The entire landscape around the launch site was almost stripped clean of everything that was not reinforced. Craters and debris now mar the land across the launch site.

When the vehicle finally exploded at the end of the test flight, debris and starship heatshield tiles were found to have been scattered across the land as well, seen here:

Over the coming days, it is certain that more tiles and other scraps of debris will be washing up on the shore.

Current Speculation and Theories of What Really Happened

DISCLAIMER: On Friday, April 28th, Elon Musk hosted a Twitter Spaces going over the flight. In it, he both confirmed and disproved a lot of speculation. A special effort has been made to denote what is confirmed at this time and what is still speculation.

The biggest culprit for most of how this flight turned out was the concrete of the OLM. As Elon said on the Twitter Spaces, the concrete did not support the thrust of B7 and subsequently shattered. As seen in this image provided by LabPadre, a massive chunk of concrete can be seen being thrown up to the same altitude as the ship quick disconnect arm.

This, coupled with the pictures showing a crater, creates a strong argument against allowing a launch with only a flat base of concrete protecting the pad, without water deluge or a flame diverter. In fairness to SpaceX, Elon publicly stated they believed the “Fondag would hold through 1 launch” given the data they collected from previous static fires, including the 31 engine static fire of B7. Unfortunately, either the data, the assumption, or potentially both, were incorrect.

If the concrete indeed shattered, the most likely mechanism to have caused this would have been imperfections and cracks in the concrete at the base of the OLM, which allowed the pressure generated by 33 raptors to seep under the concrete and shatter the foundation, which would also lift massive chunks into the air as can be seen.

The pictures in this tweet from RGV Aerial Photography provide the best views of the OLM following B7’s 31 engine full duration test. The concrete below the pad is quite damaged, with possible cracks in the direct center of the mount. It is assumed the major damage from this test would have been addressed by SpaceX before launch, but this test may have been where the cracks that doomed the pad on Integrated Flight Test first appeared.

The condition of the OLM ring itself is a critical piece of information to determine the future steps SpaceX will have to take in order to return to flight. In a previously shown Starship Gazer tweet, the doors on both the booster quick disconnect housing and OLM ring were blown open and are no longer present on the mount.

There are several possibilities as to how these doors came off. They could have been impacted by concrete ripping them off, they could have been forced off by the force of the raptor plumes, or, as the most worrying theory postulates, an overpressure event occurred in the ring. The ramifications of this range from minimal to requiring the entire ring to be replaced and scrapped. Fortunately, the possibility of a ring overpressure event is low, as only the doors on the northern side of the OLM were blown out.

Credit: Jack Beyer on Twitter

Seen in Jack Beyer’s tweet earlier mentioned (specific image above), the blast door on the southern side of the OLM ring is still perfectly attached. If an overpressure occurred, this door would have been blown out too. This bodes well that the inside of the ring may have made it through liftoff relatively unscathed.

Knowing that concrete was very much airborne and flying at great velocities, there was a lot of speculation that the three engines seen out at liftoff were due to concrete damage. This is not unfounded, as a similar incident occurred after a static fire test of Starship SN8, when flying concrete impacted the vehicle causing a loss of pneumatics. On the Twitter Spaces, Elon confirmed the true cause to be deliberate shutdown of the engines prior to liftoff. As of this time, it is unknown whether they were “deliberately shutdown” following concrete damage or from a separate issue.

When looking at the engine overlay on the SpaceX webcast, the three engines that are out are one in the center trio, and two booster engines.

Credit: SpaceX Webcast

The two booster engines are right next to each other. Both engines going out right next to each other implies a common cause, whatever that may be. Given that the center engine is out on its own and was relatively localized, the center engine likely was a separate case than the booster engines.

Credit: SpaceX/Elon Musk

In the above picture, the orientation of the engine overlay can be determent by looking at the center of the cluster. Two of the center trio can be seen running nominally, however the expected third plume is not there. When referencing the overlay, this engine is at the “bottom right” of the trio, and the two booster engines are at the “top” of the outer ring. When the perspective of the observer rotates such that the missing plume becomes the “bottom right”, we can relate the engine out overlay and the true engine positions. At liftoff, the “top” of the overlay is on the northern side of the booster, and the “bottom” on the southern. That places the two raptor boost engines that were shut off squarely on the north. This is confirmed by a Twitter video posted by Elon showing a tower view of liftoff. In it, the stack can be seen shifting to the left of the frame as it ascends. As the camera faces the gulf, which would be east, the left of the frame would be north. With two engines out on the north side of the engine cluster, the southern side would be producing more thrust and cause a sideslip towards the less powerful side.

However, this is not the only slide the vehicle was doing at the time. Seen in the embedded video below, the vehicle also was visibly leaning away from the tower during initial ascent. After some speculation that it could have been a pad avoidance maneuver (including a report published by China’s space agency), Elon confirmed on the Twitter Spaces that this slide was unintentional and was due to the engines out.

The next large topic of speculation is what occurred at the end of the flight. During the first tumble, two leaks can be seen forming very abruptly at about T+3:12.

Credit: SpaceX Webcast

The official word from SpaceX and the FAA is that the flight termination system (FTS) was activated. Elon later confirmed on the Twitter Spaces that these two leaks were indeed the FTS charges firing, yet failing to destroy the vehicle.

The FTS system on Starship is intended to explosively pierce the common dome, which acts as the wall between the liquid oxygen and liquid methane tanks. If this hole is created, the fuels will mix and, in theory, detonate the entire vehicle as they get ignited by the explosive. The Ringwatchers have an excellent Twitter thread going over finer details:

Unfortunately, the two charges were not enough to sufficiently detonate the vehicle. The exact reason of this could be many things. Perhaps a hole was created in one tank and not the other, or perhaps the explosives of the FTS did not provide a sufficient ignition source. Youtuber Scott Manley posted a short covering this possibility.

Following these two leaks appearing, the stack continued to tumble for an extended period of time. At about T+3:59, the vehicle finally exploded, ending the flight.

Credit: SpaceX Webcast

It can be noticed that on the propellant overlay that the liquid oxygen levels of the booster were very nearly depleted, or potentially completely depleted. The overlay tracked the LOX level to the level shown by T+3:24, and then did not update further. The fuel overlay decreased at what is assumed to be the normal rate, however at around T+2:50, the LOX level began draining at a much faster rate, signaling a leak. This was before the FTS possibly fired (T+3:10), meaning this leak was a vehicle failure. Knowing this, it is possible that the engines ran dry, causing a rough shutdown, and then creating an explosion that propagated up the stack.

The following images are frames captured from Cosmic Perspective’s tracking footage of the flight, posted on Twitter. It offers very high resolution footage at smooth framerates, perfect for speculation.

This footage shows the overall explosion of the vehicle began in the aft section of the booster, where the engines were.

The explosion travels up the booster, where another explosion begins at about where the FTS-caused leak would be. This is possibly the hole created by the booster’s FTS charges finally mixing propellant enough to detonate.

There is a leaked image showing the immediate aftermath of the booster exploding. The picture is of a camera from S24’s forward flap, aiming down and showing the remnants of the booster:

In a nominal FTS sequence, the entire vehicle is meant to be destroyed in a clean manner. However, about 6 rings and the gridfins can be seen remaining of the booster that managed to escape the explosion. It can also be seen that the ship and booster have at least somewhat separated. This is another topic of discussion: whether stage separation failed or was never called. Elon confirmed on the Twitter Spaces that the vehicle never deemed it safe to do so, and as such never attempted stage separation.

Further along in the video following the booster breakup, a second explosion can be seen with much more intensity. This is most likely the ship exploding, as it survived the booster explosion. The ship has not used any fuel, so it had a full vehicle’s worth of propellant when it exploded, explaining the magnitude compared to the booster which had drained nearly all of its propellant.

Given that the ship exploded after the booster, and by the leaked image also managed to separate (somewhat) cleanly, it is possible that the blue glows seen in the above image are indeed the raptor engines igniting and attempting to stabilize the ship by gimbaling. This is a very speculative theory, as there is no clear evidence other than these glows. It is also suspected that FTS activation likely kills any running flight processes, meaning the ship would not be able to command the raptors to fire even if the ship was otherwise healthy. This was unmentioned on the Twitter Spaces.

To reiterate, all analysis and assumptions made in this section are to be taken as speculation only, and not as proven fact. Elon Musk announced in a subscribers-only tweet that he would host another Twitter Spaces session to share more findings in the next few weeks.

The Path Forward

The first step will obviously be cleanup and inspections of the launch site. Workers were first seen returning to the pad the next night (April 21st) and the road was opened to the public on the 22nd. Since then, workers have been spotted surveying the OLM, and even going inside. The chopsticks and ship quick disconnect arms were moved and restored to default positions on the 24th. For the forthcoming future, cleanup and repair work will be the majority of activity at Starbase. The vertical tank farm tank replacement will be the most visible change to the surrounding site, as Elon stated on the Twitter Spaces that they will be replaced by horizontal tanks.

As for the plans following the launch, Elon has mentioned both in tweets and in the Twitter Spaces that he believes to be ready for launch again in 1 to 2 months, however, it is quite easy to say this will not happen. When it does, we can expect a new system replacing the Fondag concrete to take the force of Superheavy’s power. In response to an Eric Berger tweet, Elon mentioned the construction of a water-cooled steel plate replacing the Fondag:

On the Twitter Spaces, Elon laid out the plate system as a thick water-cooled plate that will connect to the concrete pilings of each OLM leg. He also mentioned that a proper flame trench is possible, but SpaceX is deciding against that for the time being. Sections of the plate are already in Starbase, spotted by RGV Aerial Photography:

Ideally, this steel plate will survive a launch much better than the Fondag concrete and be instrumental in allowing Starbase to facilitate the multiple launches per week SpaceX is aspiring for.

Another possible avenue for the path forward is the expansion of Starfactory. Starfactory is the intended transformation of the build site from its tents and open air bays into a proper rocket factory, much more akin to SpaceX’s factory/headquarters in Hawthorne, California.

The ring yard has also recently received labels for further-streamlined logistics, spotted by RGV. Notably, each label is prefixed by “Starfactory”.

SpaceX has recently begun preliminary construction of a second “megabay”, which will provide extra space for working on ships and boosters simultaneously. This action is required to keep up with the increasing production cadence of vehicles. In the flight test webcast, SpaceX announced their plans to complete 8 ships and 5 boosters this year alone.

To facilitate this further, the site at Masseys is also receiving more attention:

Ship 25 can be seen along with a nosecone and multiple test tanks. A small ring yard has started forming just behind the test tank on the right. S25 is hooked up to a cryo station. It is likely that Masseys will now become a regular testing site for cryogenic proofing of ships before they roll to the launch site for static fire testing and eventual launch. Previously, the suborbital pads at the launch site handled all testing of ships, including cryogenic proofing. Masseys may be taking this over to open up extra space both at the suborbital site and at the build site. In terms of space, the makeshift ring yard could also serve as an extra rocket garden, as the one at the build site is growing in number and shrinking in available space. Placing a rocket garden there could allow SpaceX to “queue up” ships for proof testing, where they sit in line before being hooked up to the cryo station, and then rolling directly to the launch site after proofing is complete.

On the topic of expansion, it also seems that the second orbital launch pad is at least in preps for construction. Lifting eyes for tower segments were seen a few weeks ago coming back to Starbase:

While lessons are being learned and repair work progresses on the first orbital pad, we may see signs in the coming months of the second orbital launch pad beginning construction, likely starting with the tower. While details are unknown, it is safe to assume this pad and tower will feature multiple significant upgrades over the first pad.

As is come to be expected of SpaceX, there is no shortage of new vehicles as well ready to take the mantle of testing now that S24 and B7 have done their part. As of this time, the presumable next pairings for flights are Ship 26 and Booster 9, as well as Ship 27 and Booster 10. Elon confirmed Booster 9’s flight assignment in the Twitter Spaces, but also said that the ship to fly with B9 is as of yet undecided. Given that the FTS system was fired and failed, we will likely see work on the FTS area of both B9 and whichever ship(s) that end up being assigned for flight. On the Spaces, Elon clarified that the FTS system will require a redesign and recertification.

Credit: Starship Gazer

Ship 26 and 27 are notable departures from the regular starship design, however this is only temporary; Ship 28 and its successors are confirmed to be “normal” ships. Both ships lack flaps and a heatshield. S26 also lacks a payload bay. Ship 24 and 25 had payload bays that were eventually sealed, however S26 was not observed to have a payload bay at all. S27 at this time does have the signature “pez dispenser” door, intended for deployment of SpaceX’s new Starlink V2 satellites. These ships are speculated to be merely dummy-ships intended to increase the testing cadence to keep up with production. SpaceX has filed with the FAA during its licensing for the test flight that the next two launches would be in configurations intended to not survive reentry, meaning the only real goal of flying 26 and 27 is achieving orbit, and for the latter, potentially deploying satellites.

Booster 9 and 10 sport major upgrades over previous boosters. They will have improved engine shielding robustness, ideally helping keep any engine failures localized instead of spreading throughout the cluster. These boosters will be the first to utilize electrical thrust vectoring control (TVC) instead of hydraulic TVC. This eliminates the need for HPUs on the booster, which may prove to be the dooming element of B7.

Credit: Starship Gazer

Credit: Starship Gazer

The HPUs on B7 had a haunting track record. They had failed multiple times and were even replaced by Booster 8’s HPUs, which ultimately led to B8 being scrapped. Depending on the true extent of any concrete damage to B7 during liftoff, the HPUs failing may hold significant blame in how the test flight resulted. Booster 9 onwards will no longer have this failure mode.

The raptor engines will now gimbal using electrical power, and this also improves their responsiveness. The hydraulically-driven raptors of old on B4 and B7 took relatively significant time to adjust their gimbal. On ETVC raptors, this issue is more than fixed as seen in this video:

When combining these new upgrades to both stage zero and the vehicles themselves, it is likely that all problems that arose during this first ever test flight will have been addressed. The booster will have no failure-prone HPUs. The launch pad will have proper deluge and flame diversion systems to hopefully not produce another crater. Even the raptor engines themselves will be more reliable; the raptors that flew on the Integrated Flight Test were well over a year old, which is quite old in SpaceX’s rapid iterative development timescale.

On the Twitter Spaces, Elon said the next flight will hopefully make it to stage separation nominally, which would signify progress from failure during booster flight to achieving a nominal booster flight. He also mentioned that the ignition sequence for launch will likely be reduced to 2.5 seconds, instead of the much longer 5-8 seconds of this flight. In his ever-present timeline optimism, Musk also stated that there is a “nearly 100% chance” that Starship will achieve orbit in the next 12 months.

In addition, Elon mentioned Starship’s status in the HLS program. Starship is slated to be humanity’s lunar lander for the first return to the lunar surface by a human since Apollo 17, in 1972. For that to remain the case, Starship will need to work by the time comes for Artemis 3, currently scheduled for 2025. Elon stated with confidence that Starship HLS will not become a holdup for Artemis 3.

Closing Thoughts

Starship gave us a spectacular first launch and has taught us plenty of lessons already. This flight has been applauded by faces and voices all over the space community, and deservedly so. A goal of just getting off the pad turned into a flight that will be remembered for ages and will be in textbooks in the future.

And even then, after such a monumental day, SpaceX is already back to work. Workers are cleaning up debris and making repairs. Ships and boosters are being produced at an ever-increasing rate. The area known as “Starbase” is growing into a proper landmark of humanity on the Earth. The era of Starship has only just begun.

Leave a Reply